In the modern world, nothing of value should go uninsured. While we often associate insurance with personal assets such as cars, homes, or health and life coverage, the role of insurance actually extends far beyond the individual.

Industrial insurance is one of the foundational pillars of our global economy.

It is not merely important but truly indispensable as it:

- Protects against catastrophic losses

- Enables financing and investment

- Facilitates international trade

- Ensures regulatory compliance

- Addresses emerging systemic risks (cyber threats, climate volatility)

- Stabilizes entire economies

Without insurance, many global industries, particularly shipping, energy, aviation, and infrastructure, would not be unable to operate at scale.

Why do I say that? Because financing by large banks will not materialize without adequate risk transfer mechanisms in place.

In 2024, global insurance premiums exceeded USD 7 trillion, representing more than 7% of global GDP. The industry grew by nearly 9% in that year alone, underscoring the increasing relevance and resilience of the industry [1] Allianz 2025. The insurance industry is growing faster than GDP!

To put this in perspective:

- Banking assets (at ~USD 200 trillion) are ~20× larger than annual insurance premiums.

- Total global financial assets (incl. banks, funds, pensions, insurers) are estimated to reach over USD 500 trillion [10].

These figures highlight the scale and interconnectedness of insurance within the broader financial system.

Let us now explore the deeper relationship between industrial insurance and global banking and how the dynamic between insurance and banking supports the financing of human life and energy.

Ps. for this blog I appreciate the input and guidance of the insurance specialist Rodney Garrard

- Why Industrial Insurance is Essential for Banking

2024 saw global insurance premiums reaching about USD 7.5 trillion, with life and health insurance accounting for around USD 4.9 trillion, and property and casualty (P&C) insurance contributing USD 2.5 trillion. Included in these P&C figures, and often underrepresented, you will find the critically important industrial insurance. It is estimated that roughly 50% of total P&C insurance coverage serves commercial purposes, with a smaller but vital fraction dedicated to industrial activities.

These industrial policies are required for securing financing from banks.

To understand the significance, consider the composition of global GDP, which in 2024, stood at ~USD 110 trillion. Industrial activity accounts for around 25-30% of this figure, forming the backbone of modern economies. Without industrial output, the service and agricultural sectors would struggle to function effectively.

Industrial activity is driven by human capital, financial systems, raw materials, and the critical aspect of energy. Although the energy sector represents less than 10% of global GDP, its relative share is increasing due to declining net-energy efficiency, particularly as wind and solar power expand. These technologies have a lower net energy efficiency (or energy return on investment (eROI)) when compared to traditional sources, with nuclear energy offering the highest eROI. For further details on this topic, please refer to our peer-reviewed publication “Schernikau & Smith 2022”

Insurance stands alongside finance as a critical enabler as it reduces friction, enhances efficiency, and unlocks scalability. Without insurance, industrial operations become riskier and more expensive. In fact, financing offered by banks for industrial projects is virtually impossible without insurance. Whether through conventional policies, government guarantees, or captive/self-insurance arrangements, risk transfer is a prerequisite.

Banks require assurance that their capital is protected against catastrophic events such as:

- Fire, explosions, or natural disasters

- Operational accidents or systemic failures

Moreover:

- Project finance and corporate lending agreements typically include covenants mandating insurance coverage

- Banking regulations (e.g., Basel III) enforce prudent risk management practices

- Syndicated loan structures often stipulate comprehensive insurance as a condition for disbursement

In short, industrial insurance is not merely a safeguard, it is a strategic enabler of industrial growth and financial stability.

2. Insurance and Banking Relating to Energy, including Coal

The past 10 years have been a roller-coaster for insurance and banking related to “industrial energy activity”. Please keep in mind that, despite the global push toward “decarbonization”, these energy sources remain foundational to modern life and the 80+% oil, coal, and gas share remains largely unchanged for over 4 decades now.

Let’s look at 4 main eras during the past decade:

- 2015–2021: Pledges & “phase-down” era

- 2022–2023: Energy-security shock & ESG backlash

- 2024: Formal reset

- 2025: Banks & insurers “back in”

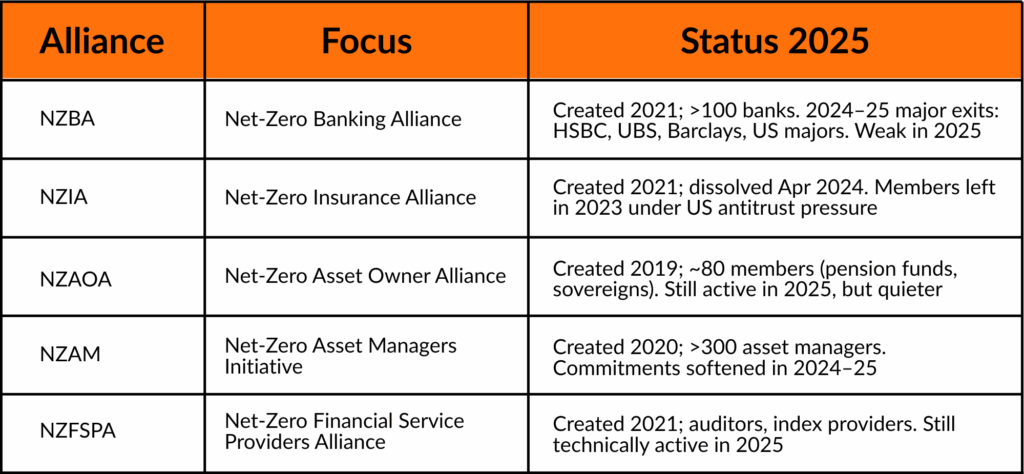

GFANZ Sub-Alliances Overview (as of 2025)

Table 1: List of “Net-Zero” finance related associations set up since 2019

2015–2021: Pledges & the “phase-out” era

We have experienced a period marked by ambitious climate pledges, ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) momentum, and increasing pressure on financial institutions to divest from fossil fuels. Many insurers and banks announced restrictions or even complete exits from coal and other higher-CO2-emission sectors. The narrative was dominated by “decarbonization” targets and net-zero commitments.

The 2015 Paris Agreement lead to a wave of voluntary “net-zero” pledges across the finance industry. In 2021 many joined the UN-backed Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) and two sub-alliances, a) for banks the Net-Zero Banking Alliance NZBA, and b) for insurers the Net-Zero Insurance Alliance NZIA.

For coal in particular, it has been an uphill battle. Even though coal makes up 25% of all energy and over 35% of global electricity, insurers clamped down on insuring coal (2018–2020) with European groups (AXA, Allianz, Swiss Re, etc.) rolling out widespread coal and other fossil fuel restrictions; Lloyd’s of London issued a 2020 market pledge to phase out thermal-coal & Arctic underwriting over time.

2022–2023: Energy-security shock & ESG backlash

Geopolitical and economic shocks, particularly Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine in 2022 fired the flames of a global LNG/oil/gas build-out leading to record coal prices due to coal scarcity. As a result, coal and gas experienced a resurgence, and ESG frameworks came under scrutiny for their unintended consequences on energy affordability and reliability.

We saw a large-scale reshuffling, resulting from sanctions and a global reassessing of energy security, across the energy and commodity markets.

Blackouts in Pakistan and Bangladesh effecting hundreds of millions of people occurred. Why?… because Europe was able to pay the higher price for LNG cargos resulting in “energy” being “diverted” away from poorer developing nations. Within the coal market, despite the high 2022 prices, this was not the case.

This led to an exodus of insurers from the infamous Net-Zero Insurance Alliance NZIA in 2023. Furthermore US political antitrust pressure caused a mass departure from the NZIA by major players such as Munich Re, Zurich, Swiss Re, AXA, Allianz, SCOR leaving the alliance hollowed out. Reuters 2023 [2].

2024: Formal reset

By 2024, a more pragmatic approach began to emerge. Policymakers, financiers, and insurers started to recalibrate their strategies, acknowledging the need for a balanced energy mix. The focus shifted from blanket exclusions to risk-based underwriting and transitional financing models. Industrial energy, including coal, was no longer treated as a monolith but assessed in terms of regional context, technological maturity, and emissions trajectory.

In April 2024 the Net-Zero Insurance Alliance was finally dissolved and renamed as UNEP’s Forum for Insurance Transition to Net-Zero. FIT, see [3]. In effect the alliance approach softened substantially, as various NGOs documented that Lloyd’s market and big global carriers continue to underwrite fossil projects despite prior pledges. Of course, policies vary widely by line and geography.

2024 was a year where “Renewables” experienced significant insurance losses (i.e. hail on solar, lightning on wind) pushing premiums up by 20–40%, making fossil portfolios comparatively attractive to some underwriters.

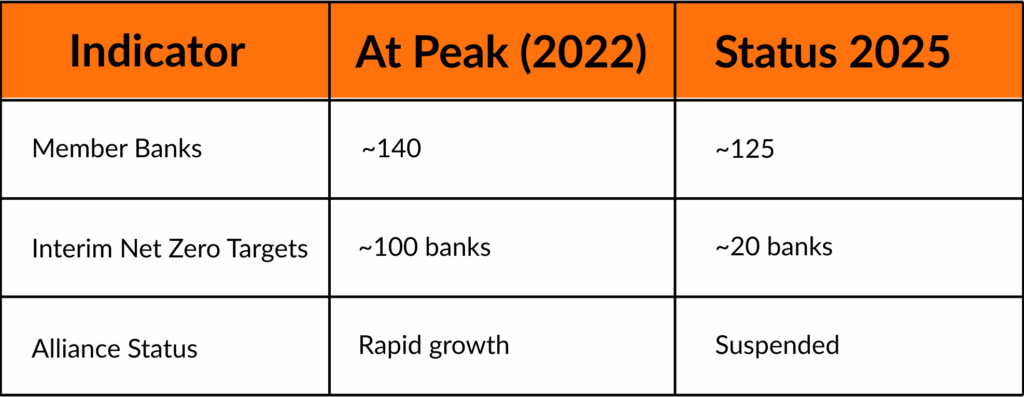

Additionally, major banks quit the Net-Zero Banking Alliances NZBA

- JPMorgan Chase (U.S.) – announced exit Oct 2023.

- Bank of America (U.S.) – exit confirmed Dec 2023.

- Morgan Stanley (U.S.) – exit Jan 2024.

- Goldman Sachs (U.S.) – exit Jan 2024.

- Wells Fargo (U.S.) – exit Feb 2024.

- HSBC (U.K.) – exit July 2025, citing competitive and legal concerns.

These exits collectively represent over $15 trillion in banking assets, roughly one-fifth of global banking assets originally covered by NZBA.

2025: Banks & insurers “back in”

In 2025, we are witnessing a cautious but decisive return of banks and insurers to the previously abandoned industrial energy sector. This includes selective re-entry into coal-related activities, particularly where modern technologies are at play, or where energy security imperatives override ESG constraints. The emphasis is now on measured engagement, risk mitigation, and “transitional support”, rather than outright exclusion.

The UN banking alliance NZBA was finally suspended as big members exited (late-2024/2025) and as withdrawals by US industry leaders and later HSBC, UBS, Barclays and others, hammering the proverbial nail into the coffin.

Table 2: NZBA at its Peak vs. Today, Source [5]

Today, banks and insurers are progressively recognizing that “net-zero” plans cause conflicts that have legal and moral ramifications

- Legal/antitrust concerns: fear that coordinated fossil-fuel restrictions could be seen as collusion.

- Political/regulatory pressures: U.S. Republican state lawsuits and U.K. competition regulators raised scrutiny.

- Fiduciary duty conflicts: banks argued rigid NZBA commitments conflicted with serving shareholder interests and actually conflicting humanity’s progress. “Activists” start suing management because “net-zero” promises cannot be kept.

- Competitive risk: fear of ceding market share to non-aligned rivals (esp. Chinese banks).

Despite climate pledges, insurers are regaining their appetite for coal. After an initial pull-back from the fossil fuels, US based Chubb is now the lead reinsurer of an entirely coal-fueled plant in Vietnam (Financial Times [4]). Lloyds recently said “the corporation would no longer discourage insurers operating in the market from underwriting coal and other fossil fuel projects.” (The Guardian [5]).

FastCompany [6] reported that fossil fuel companies accounted for 4.4% of the investment portfolio of the insurance industry in 2023, up from 3.8% in 2014. Two insurance giants, Berkshire Hathaway and State Farm, increased their fossil fuel positions by around $200 billion during the same period. This trend continued throughout 2024 and 2025.

Banks that continue to support conventional energy projects include JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America, Barclays, Well Fargo, Mizhuho, MUFG, SMBC, Barclays, Santander, BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, and many others.

This re-engagement by insurers and banks shows a wide-spread recalibration of energy policy and financial risk management leaning more towards cautiously balancing “environmental commitments” with energy security, economic stability, and regional development needs.

3. “Extreme Weather” Insurance

“Extreme weather events” have become a hot topic in both media coverage and now increasingly, insurance risk assessments. While headlines often rely on the dramatic nature of these events, partly because “bad news sells”, there is a growing body of evidence that does not support the “doomsday” narrative of, for example, hurricanes which are often cited as the poster child of climate changes impacts.

- UN May 2025: Real cost of disasters is 10 times higher than previously thought, says UN

- CNN Jul 2025: Climate catastrophes are creating a ‘new market reality’ for insurance carriers

- BBC Dec 2024: A year of extreme weather that challenged billions

As figure 2 shows, insured losses from natural catastrophes have consistently exceeded USD 100 billion annually for several years. This trend reflects not only the intensity of weather events but also the growing concentration of assets in vulnerable regions, especially around coastal areas.

Figure 2: 10-year catastrophe losses, insured and uninsured (WEF, Source [7])

To put these losses into perspective, let us not forget that in 2024 global insurance premiums amounted to ~USD 7.5 trillion showing a steady rise from about USD 3.4 trillion in 2005. Catastrophe losses are highly volatile ranging from USD 27 billion (2009) to peaks over USD 140 billion in 2017, 2022, and 2024.The ratio of catastrophe losses to total premiums, mostly remained steady between 1–2%, increasing to 2–3% during the bad years.

Both 2023 and 2024 have been highly profitable years for insurance companies despite the “disaster loss rise” that mainstream media repeatedly points out.

Another interesting observation is that when you normalize natural disaster losses by GDP you see an entirely different picture, see Figure 3. In fact, despite the years 2005 and 2017, there is an overall declining trend in GDP adjusted disaster losses.

It is also quite logical seeing that the amount of damage that can be created by an extreme weather event is much higher in absolute terms, but we are mitigating the risk much more effectively and in relative terms, our lives are safer. Coasts areas are simply populated more densely, and any storm will therefore hit a much larger population and asset base than 50 years ago.

By the way, the same is true for natural disaster deaths. Humans, on average, have never been safer from natural disaster than we are today, due to the risk mitigation, health, and infrastructure that we are lucky enough to have access to. According to Our World in Data and EMDAT, human casualties from natural disasters is down by a factor of 14 from a hundred years ago..

Figure 3: Global Weather Disaster Losses as % of GDP until 2024. Source: Prof Pielke [8]

4. Responsibilities of Insurance Companies and Banks

Back to energy. It is essential to recognize that over 80% of our total primary energy comes from oil, coal, and natural gas. Insuring and financing conventional energy projects is highly profitable for both banks and insurance companies, not only due to scale but also because of the elevated risk premiums they can command.

However, there are other reasons we need to consider on why insurance and banking institutions should continue to support all forms of energy.

Systemic Dependence on Conventional Energy

When a financial institution declares, “We will no longer fund coal or gas,” it is not merely making a business decision, it is also essentially saying that no one should fund coal or gas. If everyone were to follow suite, the consequences would be severe and immediate. Industrial operations would slow, disrupting supply chains and manufacturing, energy shortages would emerge, particularly in regions already lacking access to energy infrastructure and human lives would be at risk, due to lack of heating, food production, and essential services.

Despite two decades of investment in the energy transition, wind and solar still represent a small fraction of total energy supply. Their low energy return on investment (eROI) and intermittency limit their ability to replace dispatchable conventional sources at scale.

Fiduciary and Moral Obligations

Insurance and banking institutions have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders to pursue profitable ventures. But they also have a moral obligation to support the infrastructure that sustains human life and economic stability. Energy is not optional but rather foundational.

Supporting conventional energy does not preclude investment in so called “renewables”. However, recent experience has shown that returns on wind and solar investments have been, in many cases, negative and capital intensity per unit of energy is significantly higher for wind and solar (see Figure 4). Dispatchable, on-demand energy remains the most reliable and scalable solution.

Rather than abandoning conventional energy, financial institutions should adopt a balanced strategy including the underwriting and financing of reliable energy systems, including oil, coal, gas, and nuclear.

In doing so, insurers and banks not only fulfill their commercial mandates but also uphold their role as enablers of societal resilience and continuity.

Yes, we have to invest in more R&D to find a long-term solution with high energy density and that is economically and environmentally more sustainable than our current systems. Until we have this alternative solution, we should IN-vest in our existing systems to make them cleaner and more economical , and not DI-vest from them.

5. Summary

As you can see now, insurance is so much more than just protection for our homes, cars, or health. It is a crucial part of the global economy. Industrial insurance, doesn’t just insure against loss, but it also enables financing and investment as well as meets regulatory compliance. Without insurance, banks refrain from funding large projects, resulting in industries such as shipping, energy, and infrastructure failing to operate at scale. In 2024, global insurance premiums reached USD 7.5 trillion, which is more than 7% of global GDP.

The connection between banking and insurance is a fundamental one as banks require the transfer of insured risk to finance projects. This turns industrial insurance into a strategic enabler of growth and stability which is especially critical in the energy sector, where over 80% of global demand is still met by coal, oil and gas. The recent shift in direction by major insurers and reinsurers like Lloyd’s of London and Chubb, has had a significant impact on the availability and pricing of coal insurance.

With more insurers willing to underwrite coal, gas, and oil risks, competition has sparked once again leading to more favourable pricing for fossil-fuel-related insurance. As insurers are not returning blindly but rather selectively showing appetite for:

- Modern coal facilities with advanced emissions controls

- Projects tied to national energy security

- Assets in jurisdictions with stable regulatory frameworks

- Reputational Risk Management

Simultaneously, wind and solar projects and their derivatives became costly to insure, with losses from hail, lightning, and other risks driving premiums up by 20-40%, as fossil fuel portfolios regained their appeal. Now in 2025, banks and insurers are once again financing and underwriting coal, oil, and gas projects.

According to the press, extreme weather losses remain high, but when adjusted for GDP and population growth, disaster risks are comparatively lower than the headlines suggest. Human lives today are safer from natural disasters than ever before, thanks to improved infrastructure and risk mitigation.

Considering all of the information at hand, I am of the opinion that banks and insurers have not only a fiduciary duty to shareholders but also a moral responsibility to support reliable, dispatchable, on-demand energy. Investment in R&D should continue, because abandoning conventional energy prematurely would threaten societal stability and human well-being. Until a scalable, energy dense, and sustainable alternative is found, the world must invest in improving existing energy systems rather than divesting from them.

With banks continuing to finance conventional energy projects, and the renewed insurance appetite helps align risk transfer mechanisms with lending practices, a critical alignment for project finance, syndicated loans, and infrastructure development is taking place.

Links and Resources

[1] Allianz 2025, Allianz Global Insurance Report 2025: Rising Demand for Protection,” Allianz.Com, May 2025, (link)

[2] Reuters 2023: Insurers’ Climate Alliance Loses Nearly Half Its Members after More Quit,” Business, Reuters, May 2023, (link)

[3] New UN Multistakeholder Forum to Drive Progress on the Insurance Transition to Net Zero, April 2024, (link)

[4] Financial Times: Insurers Regain Appetite for Coal despite Climate Pledges,” Energy Source, Financial Times, July 2025, (link)

[5] The Guardian: New Lloyd’s Boss Signals Shift on Insuring Fossil Fuels, Business, The Guardian, September 2025, (link)

[6] “Insurance Companies Are Financing Oil and Gas—Even as Climate Change Is Pummeling Their Bottom Line,” Fast Company, January 2025, (link)

[7] WEF: Climate Events Have Cost $162b in 2025. Insurance Covered Most,” World Economic Forum, August 2025, (link)

[8] Pielke: Disaster Loss ‘Climate Change Is Showing Its Claws,’” Substack newsletter, The Honest Broker, January 2025, (link)

[9] Schernikau based on IEA: World Energy Investment 2025 – Analysis (2025), (link)

[10] “Why the Net Zero Banking Alliance Collapsed and What It Means for Sustainable Finance | Blog | ASUENE | The Enterprise Climate Cloud Platform | Carbon Calculation Decarbonizated SaaS,” ASUENE, August 29, 2025, (link)

[11] Financial Times: How Large Are Global Financial Assets?,” FT Alphaville, Financial Times, July 2025, (link)